36. Dare to Disturb the Universe: Madeleine L’Engle on Creativity, Censorship, Writing, and the Duty of Children’s Books

“We find what we are looking for. If we are looking for life and love and openness and growth, we are likely to find them. If we are looking for witchcraft and evil, we’ll likely find them, and we may get taken over by them.”

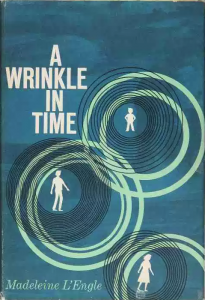

On November 16, 1983 — just two weeks before her 65th birthday and twenty years after winning the prestigious Newbery Medal — Madeleine L’EngleMadeleine L’Engle (November 29, 1918–September 6, 2007), author of the timeless classic A Wrinkle in Time, delivered a magnificent lecture at the Library of Congress. To celebrate Children’s Book Week the following year — the year I was born — the Library’s Center for the Book and the Children’s Literature Center published L’Engle’s talk as a slim and, sadly, long out-of-print volume titled Dare to Be Creative! (public library) — a magnificent manifesto of sorts on writing, writers, and children’s books, as well as a bold and beautifully argued case against censorship.

On November 16, 1983 — just two weeks before her 65th birthday and twenty years after winning the prestigious Newbery Medal — Madeleine L’EngleMadeleine L’Engle (November 29, 1918–September 6, 2007), author of the timeless classic A Wrinkle in Time, delivered a magnificent lecture at the Library of Congress. To celebrate Children’s Book Week the following year — the year I was born — the Library’s Center for the Book and the Children’s Literature Center published L’Engle’s talk as a slim and, sadly, long out-of-print volume titled Dare to Be Creative! (public library) — a magnificent manifesto of sorts on writing, writers, and children’s books, as well as a bold and beautifully argued case against censorship.

L’Engle begins by making a point about children’s capacity for handling darker emotions that would’ve made Tolkien proud, one that Maurice Sendak has also asserted and Neil Gaiman has recently echoed. L’Engle observes:

The writer whose words are going to be read by children has a heavy responsibility. And yet, despite the undeniable fact that the children’s minds are tender, they are also far more tough than many people realize, and they have an openness and an ability to grapple with difficult concepts which many adults have lost. Writers of children’s literature are set apart by their willingness to confront difficult questions.

For that reason, L’Engle argues, editors and publishers often attempt to remove these difficult questions from the get-go — a form of preventative censorship, the kind the great Ursula Nordstrom meant in her witty and wise lament that children’s book publishing was run largely by “mediocre ladies in influential positions” unwilling to deviate from the safe route. L’Engle recounts her own brave resistance to such pressures, even in the face of repeated rejection:

Many years ago, when A Wrinkle in Time was being rejected by publisher after publisher, I wrote in my journal, “I will rewrite for months or even years for an editor who sees what I am trying to do in this book and wants to make it better and stronger. But I will not, I cannot diminish and mutilate it for an editor who does not understand it and wants to weaken it.”

Now, the editors who did not understand the book and wanted the problem of evil soft peddled had every right to refuse to publish the book, as I had, sadly, the right and obligation to try to be true to it. If they refused it out of honest conviction, that was honorable. If they refused it for fear of trampling on someone else’s toes, that was, alas, the way of the world.

Though she did eventually find a publisher who believed in the book heart and mind, this still left the question of the general public, where ignorant self-appointed censors lurk. Decades before the golden age of mindless online comments and TLDR-mentality, L’Engle recounts a tragicomic incident:

Recently I was lecturing in the Midwest, and the head librarian of a county system came to me in great distress, bearing an epistle composed by one woman, giving her all the reasons she should remove A Wrinkle in Time from the library shelves. This woman, who had obviously read neither Wrinkle nor the Bible carefully, was offended because she mistakenly assumed that Mrs. What, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which were witches practicing black magic. I scrawled in the margin that if she had read the text she might have noted that they were referred to as guardian angels. The woman was also offended because they laughed and had fun. Is there no joy in heaven! The woman belonged to that group of people who believe that any book which mentions witches or ghosts is evil and must be banned. If these people were consistent, they would have to ban the Bible: what about the Witch of Endor and Samuel’s ghost?

The woman’s epistle went on to say that Charles Wallace knew things that other people didn’t know. “So did Jesus,” I scrawled in the margin. She was upset, because Calvin sometimes felt compulsions. Don’t we all? This woman obviously felt a compulsion to be a censor. Finally I scrawled at the bottom of the epistle that I truly feared for this woman.

In a sentiment that Milton Glaser would come to echo decades later in his beautiful meditation on the universe, L’Engle drives home the point of this parable:

We find what we are looking for. If we are looking for life and love and openness and growth, we are likely to find them. If we are looking for witchcraft and evil, we’ll likely find them, and we may get taken over by them.

She adds an important disclaimer on the difference between censorship and discernment:

We all practice some form of censorship. I practiced it simply by the books I had in the house when my children were little. If I am given a budget of $500 I will be practicing a form of censorship by the books I choose to buy with that limited amount of money, and the books I choose not to buy. But nobody said we were not allowed to have points of view. The exercise of personal taste is not the same thing as imposing personal opinion.

With a riff on T.S. Eliot’s famous line from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” — “Do I dare disturb the universe?” — L’Engle reflects on the role of reading, and taste in reading, in her own life:

The stories I cared about, the stories I read and reread, were usually stories which dared to disturb the universe, which asked questions rather than gave answers.

I turned to story, then, as now, looking for truth, for it is in story that we find glimpses of meaning, rather than in textbooks. But how apologetic many adults are when they are caught reading a book of fiction! They tend to hide it and tell you about the “How-To” book which is what they are really reading. Fortunately, nobody ever told me that stories were untrue, or should be outgrown, and then as now they nourished me and kept me willing to ask the unanswerable questions.

She offers another autobiographical anecdote that sheds light on how our righteousness works:

One time I was in the kitchen drinking tea with my husband and our young son, and they got into an argument about ice hockey. I do not feel passionate about ice hockey. They do. Finally our son said. “But Daddy, you don’t understand.” And my husband said, reasonably, “It’s not that I don’t understand, Bion. It’s just that I don’t agree with you.”

To which the little boy replied hotly, “If you don’t agree with me, you don’t understand.”

I think we all feel that way, but it takes a child to admit it.

That righteousness — which bears the markings of the fundamentalism Isaac Asimov memorably bemoaned — is what L’Engle believes flattens culture and robs us of its richness:

We need to dare disturb the universe by not being manipulated or frightened by judgmental groups who assume the right to insist that if we do not agree with them, not only do we not understand but we are wrong. How dull the world would be if we all had to feel the same way about everything, if we all had to like the same books, dislike the same books…

Perhaps some of this zeal is caused by fear. But as Bertrand Russell warns, “Zeal is a bad mark for a cause. Nobody had any zeal about arithmetic. It was the anti-vaccinationists, not the vaccinationists, who were zealous.” Yet because those who were not threatened by the idea of vaccination ultimately won out, we have eradicated the horror of smallpox from the planet.

L’Engle examines the heart of zeal, often driven by our failure to grant ourselves the “uncomfortable luxury” of changing our minds. She agrees with Bertrand Russell’s assertion that we are zealous when we aren’t completely certain we are right, in a reflection that brings it all back to children’s books and the art of disturbing the universe:

When I find myself hotly defending something, wherein I am, in fact, zealous, it is time for me to step back and examine whatever it is that has me so hot under the collar. Do I think it’s going to threaten my comfortable rut? Make me change and grow? — and growing always causes growing pains. Am I afraid to ask questions?

Sometimes. But I believe that good questions are more important than answers, and the best children’s books ask questions, and make the reader ask questions. And every new question is going to disturb someone’s universe.

Like Asimov, who found in science fiction a way to make points he otherwise couldn’t, L’Engle sees in fiction a sandbox, a safe place for asking those uncomfortable questions:

Writing fiction is definitely a universe disturber, and for the writer, first of all. My books push me and prod me and make me ask questions I might otherwise avoid. I start a book, having lived with the characters for several years, during the writing of other books, and I have a pretty good idea of where the story is going and what I hope it’s going to say. And then, once I get deep into the writing, unexpected things begin to happen, things which make me question, and which sometimes really shake my universe.

L’Engle makes a heartening case for the presently accepted idea that what makes science interesting — what makes it meaningful and culturally significant — isn’t its certitude and all-knowingness, but its “thoroughly conscious ignorance,” the very not-knowing that Donald Barthelme memorably argued was also at the heart of writing. L’Engle reflects:

I’m frequently asked about my “great science background,” but I have no science background whatsoever. I majored in English Literature in college. We were required to take two languages and one science or two sciences and one language, so of course I took two languages and psychology. Part of my reluctance about science was that when I was in school, science was proud and arrogant. The scientists let us know that they thought they had everything pretty well figured out, and what they didn’t know about the nature of the universe, they were shortly going to find out. Science could answer all questions.

[…]

Many years later, after I was out of school, married and had children, the new sciences absolutely fascinated me. They were completely different from the pre-World War II sciences, which had answers for everything. The new sciences asked questions. There was much that was not explainable. For everything new that science discovered, vast areas of the unknown were opened. Sometimes contemporary physics sounds like something out of a fairy tale: there is a star known as a degenerate white dwarf and another known as a red giant sitting on the horizontal branch. Can’t you imagine the degenerate white dwarf trying to get the red giant of the horizontal branch?

L’Engle ties this not-knowing back to the question of censorship in writing for children:

Perhaps one of the most important jobs of the writer whose books are going to be marketed for children is to dare to disturb the universe by exercising a creative kind of self-censorship. We don’t need to let it all hang out. Sure, kids today know pretty much everything that is to be known about sex, but we owe them art, rather than a clinical textbook. Probably the most potent sex scene I have ever read is in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary where Emma goes to meet her lover, and they get in a carriage and draw the shades, and the carriage rocks like a ship as the horses draw it through the streets. How much more vivid is what the imagination can do with that than the imagination-dulling literal description!

I do not believe that any subject is in itself taboo, it is the way it is treated which makes it either taboo or an offering of art and love.

It is the writer’s duty, L’Engle argues, to continue reclaiming complex ideas from the grip of simplistic taboo:

The first people a dictator puts in jail after a coup are the writers, the teachers, the librarians — because these people are dangerous. They have enough vocabulary to recognize injustice and to speak out loudly about it. Let us have the courage to go on being dangerous people.

[…]

So let us look for beauty and grace, for love and friendship, for that which is creative and birth-giving and soul-stretching. Let us dare to laugh at ourselves, healthy, affirmative laughter. Only when we take ourselves lightly can we take ourselves seriously, so that we are given the courage to say, “Yes! I dare disturb the universe.”

The whole of Dare to Be Creative!, should you be so luck to track down a surviving copy, is a masterpiece of thought and spirit more than worth a read.