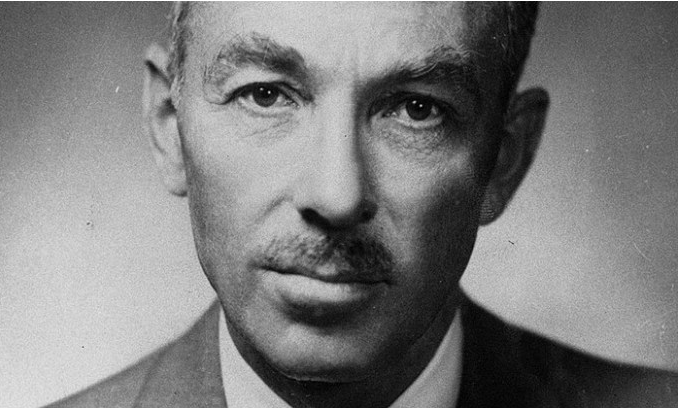

28. E.B. White on How to Write for Children and the Writer’s Responsibility to All Readers

“Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down.”

The loving and attentive reader of children’s books knows that the best of them are not one-dimensional oversimplifications of life but stories that tackle with elegant simplicity such complexities as uncertainty, loneliness, loss, and the cycle of life. And anyone who sits with this awareness for a moment becomes suddenly skeptical of the very notion of a “children’s” book. Maurice Sendak certainly knew that when he scoffed in his final interview: “I don’t write for children. I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’” Seven decades earlier, J.R.R. Tolkien had articulated the same sentiment, with more politeness and academic rigor, in his terrific essay on why there is no such thing as writing “for children.” But one of the finest, most charming and most convincing renunciations of the myths about writing for children comes from E.B. White, nearly two decades after he sneezed Charlotte’s Web.

In a 1969 interview, included in the altogether unputdownable The Paris Review Interviews, vol. IV (public library) — which also features wonderfully wide-ranging conversations with Haruki Murakami, Maya Angelou, Ezra Pound, Marilynne Robinson, William Styron and more — White turns his formidable amalgam of wit and wisdom to our culture’s limiting misconceptions about storytelling “for children.”

In a 1969 interview, included in the altogether unputdownable The Paris Review Interviews, vol. IV (public library) — which also features wonderfully wide-ranging conversations with Haruki Murakami, Maya Angelou, Ezra Pound, Marilynne Robinson, William Styron and more — White turns his formidable amalgam of wit and wisdom to our culture’s limiting misconceptions about storytelling “for children.”

When the interviewer asks whether there is “any shifting of gears” in writing children’s books, as opposed to the grownup nonfiction for which he is best known, White responds with the rare combination of conviction and nuance:

Anybody who shifts gears when he writes for children is likely to wind up stripping his gears. But I don’t want to evade your question. There is a difference between writing for children and for adults. I am lucky, though, as I seldom seem to have my audience in mind when I am at work. It is as though they didn’t exist.

Echoing Ursula Nordstrom — the visionary editor and patron saint of childhood who brought to life not only Charlotte’s Web but also such classics as Goodnight Moon, Where the Wild Things Are, and The Giving Tree, and who famously insisted that children never want a blunt creative edge — White adds:

Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time. You have to write up, not down. Children are demanding. They are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. They accept, almost without question, anything you present them with, as long as it is presented honestly, fearlessly, and clearly. I handed them, against the advice of experts, a mouse-boy, and they accepted it without a quiver. In Charlotte’s Web, I gave them a literate spider, and they took that.

Long before psychologists knew that language is central to how human imagination evolves, White is especially adamant about the blunting of language:

Some writers for children deliberately avoid using words they think a child doesn’t know. This emasculates the prose and, I suspect, bores the reader. Children are game for anything. I throw them hard words, and they backhand them over the net. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention. I’m lucky again: my own vocabulary is small, compared to most writers, and I tend to use the short words. So it’s no problem for me to write for children. We have a lot in common.

Like C.S. Lewis, who contemplated what writing for children reveals about the key to authenticity in all writing, White extrapolates the writer’s responsibility to all audiences:

A writer should concern himself with whatever absorbs his fancy, stirs his heart, and unlimbers his typewriter… A writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error. He should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life.

[…]

A writer must reflect and interpret his society, his world; he must also provide inspiration and guidance and challenge. Much writing today strikes me as deprecating, destructive, and angry. There are good reasons for anger, and I have nothing against anger. But I think some writers have lost their sense of proportion, their sense of humor, and their sense of appreciation. I am often mad, but I would hate to be nothing but mad: and I think I would lose what little value I may have as a writer if I were to refuse, as a matter of principle, to accept the warming rays of the sun, and to report them, whenever, and if ever, they happen to strike me.

The Paris Review Interviews, vol. IV is a treasure trove in its totality. Complement this particular gem with E.B. White on the future of reading, what makes a great city, his satirical take on the difference between love and passion, and his beautiful letter to a man who had lost faith in life.